In this section we focus on further developing your Strategies for deploying skills effectively. You may know a wide range of skills, but how do you use them reliably under pressure?

We will also look at some skills Concepts that are harder to use at race speed.

These approaches rely on you having mastered a Basic Navigation Routine and understanding a wide range of skills concepts, that you can draw on as needed. This discussion assumes you understand and can use the skills discussed in the Skills Tool Kit and other skills discussed in the Intermediate section.

It is worth reviewing the Intermediate section if there is any doubt in your mind as to whether you have mastered skills up to that level. This video by Simon Eklov (O-Ringen TV) and Janne Troeng shows the level that you can aim to be at with your skills at an Advanced level – A really hard leg in Lunsen (Lunsen is a forest area in Sweden). In Swedish with English sub-titles. (If the link does not go straight to the video, choose No. 19 En riktigt svår sträcka i Lunsen from the playlist)

Link to first video in playlist Learn to orienteer with Janne Troeng

If what Janne Troeng has demonstrated in this video seems beyond your ability at present, it is still worth reading more in this section, so that you have a range of ideas you can work towards implementing.

The Navigation Model that underpins Better Orienteering – some more detail

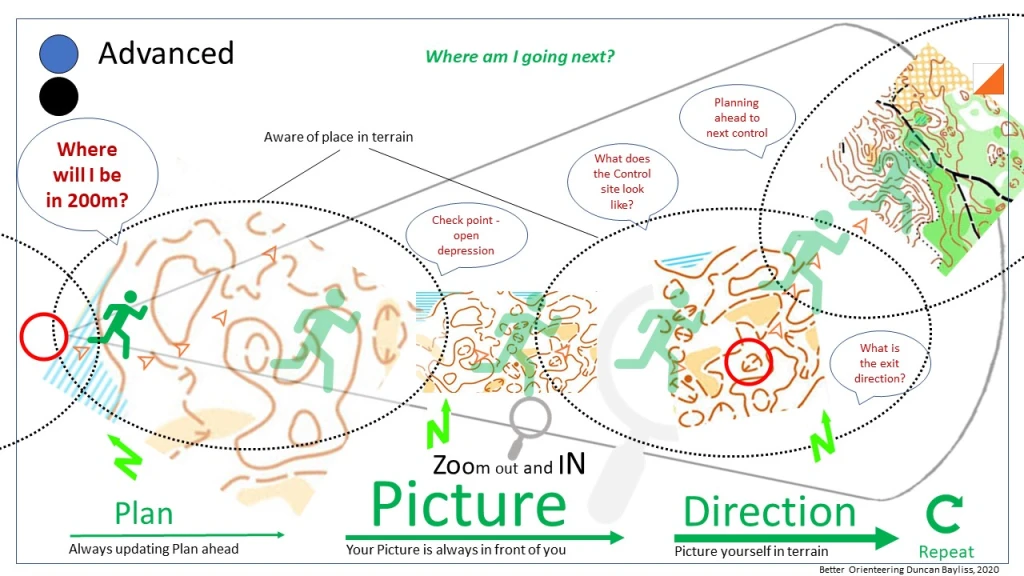

Plan – Picture – Direction

In the Intermediate section, this model, Plan – Picture – Direction, was introduced to provide an easy to remember way to draw together the elements of navigation.

The model can be expanded and mapped against what is covered throughout Better Orienteering to show the skills that you are drawing on when using Plan – Picture – Direction.

The terms Plan, Picture and Direction are drawn from Kris Jones’ model, adapted to this schematic diagram. The aim is to give a very simple memory aid for navigation e.g. Plan – Picture – Direction and to link to it to the other elements of navigation you need to understand and use when orienteering.

You should have enough experience and understanding of orienteering at this point to be able to evaluate what you understand of this model.

It is worth noting that the terms Plan, Picture and Direction are used in a slightly different way than in Kris Jones’ model. For analysis of orienteering performance, in his model, they they are expanded to Route Choice – Plan – Direction – Picture – Execution. (See the website, Elevate.run as discussed under the Advanced Analysis section of Better Orienteering.)

Over many years, some terms such as Attack Point have reached a stable definition in orienteering discussions, whereas there is quite a bit of variability and fluidity in how others terms such as Plan or Visualise are used. I have tried to be consistent within Better Orienteering as far as I can, but other sources and books on orienteering do vary in how some terms are used.

In Better Orienteering the structure of skills is discussed under 3 themes; Routines, Concepts and Strategies. The sections of Better Orienteering are mapped against these themes below. The table is not exhaustive.

Routines are things you should do for every race to be successful

Concepts are understood and used flexibly on a ‘mix and match’ basis as needed in a race

Strategies are ways you learn to make sure you can use the concepts and skills you have mastered reliably every time

When analyzing your orienteering performance you can try to identify where you are losing time and why it is happening. At an Advanced level you should have minimal time losses caused by your routines and use of skills concepts.

For example, if you keep making mistakes that are being caused by not keeping strictly to a rock solid Basic Navigation Routine, then you need to practice that and repeat it until it becomes automatic. Its like a golfer always swinging the club in the same way on muscle memory. You need to practice it until it happens without thinking about it.

Or, if you needed to relocate regularly because you did not use the right navigation concepts as described in the Intermediate level Skills Tool Kit, then practice route planning (see Intermediate section) discuss your routes a lot with other experienced orienteers and analyse your routes and navigation carefully to make sure you are using the right mix of skills in an effective way.

If you have a reliable routine and understand and can use a wide range of orienteering navigation concepts appropriately, then you will probably find that focusing on the strategies you use to deploy them will help a lot.

Remember, it is possible to be self-taught orienteer who is a very competent and reliable navigator and also a fit runner, but still be a fairly slow orienteer overall! (I know many people like this). Joining it all up and making sure your navigation flows well takes both lots of practice and also careful attention to what you are doing that slows down your navigation in races. This is why elite orienteers spend a lot of time practicing specific skills such as control picking and control flow, where you find and move quickly through lots of controls close together, trying to minimize any slowing down into and through controls without making any mistakes. You learn to fine tune the careful balancing act of running speed and navigation.

If you are still struggling with implementing a totally reliable navigation routine and often look at a race afterwards and see you could have used better mix of navigation concepts such as Aiming Off, then your orienteering is still at an Intermediate level. If you are a very fit runner you may still win some races, but there will be a lot of time losses that could have been avoided that would make you even faster. If you are honest and can identify how you could have saved 30 seconds per control for 20 controls, could you really run 10 minutes faster just by more fitness? But maybe you can gain that time with good technique.

The Better Orienteering Navigation model is more than just Plan, Picture, Direction

The next info-graphic summarizes what is covered across Better Orienteering and how it is related to the overall process of doing orienteering from preparing for a race through navigation to post-race analysis. It gives an overview of what underpins orienteering as a complete process. Successful orienteering navigation starts before the race, and continues afterwards in analysis and training.

The graphics for just the Better Orienteering Navigation model can be downloaded here:

These graphics are also included in the Better Orienteering Summary

The most important thing to understand with navigation is that you need to build up your orienteering starting with a foundation of basic techniques that must be laid correctly. Everything you do is built on that foundation and if you get it wrong you will be orienteering badly for a long time. Then a range of skills concepts and strategies are added to your personal Tool Kit.

Once you have the basics working well you can think about the whole experience of orienteering starting from researching the map and previous courses through the race itself, to analysing your performance afterwards. You can work on a range of strategies to use your skills knowledge and join it all up effectively.

As your skills progress, improving your Visualisation is probably the most important thing, so that you are reliably seeing 3D terrain in your mind from what you see on the 2D map. Contours must come alive from the map! You also need to learn to always read the map on the run.

You then need to keep analysing your performance and identifying what to work on.

source: https://www.tovealexandersson.se/

Strategies

Assuming you have a reliable navigation routine and understand all the skills concepts discussed across Better Orienteering then it is worth considering what strategies you can use to put them into practice.

Orienteering styles do vary, there is no single right way to navigate

I tend to take a lot of accurate bearings on a thumb compass, where I take the time to rotate the housing, rather than just a rough bearing lining the needle up with the north lines on the map. It can take a couple seconds more to take the accurate bearing. For many orienteers, if their eyesight permits, then simply keeping the map lined up with north is all they need and they rarely take an accurate bearing. I take accurate bearings because my eyesight is no longer up to reading fine detail on the map whilst running through terrain and I was loosing too much time stopping to focus on the map, whereas I can see the compass clearly enough and some detail of the map and can move further with a picture of the map in my head before I need to stop again, saving time overall. It is frustrating, but the days of reading the map whilst still running regardless of the terrain are over.

So, issues such as eyesight and how well developed your map memory is, will affect the style of orienteering you develop. This will change over time and needs re-evaluating. Try not to get stuck in habits where you never think about how you are doing things! There is always room for improvement.

Identify a virtual corridor to track within

Following on from the point about using bearings, I often have in mind a virtual Corridor for a section of a leg with the shape of the terrain and what I am aiming for and I use the compass to keep me roughly on line. Since the bearings are taken quickly, I am expecting to always drift to one side or the other of the corridor. The leg is then achieved in a series of curves. I will look for a runnable line on the ground which will also cause wiggles in the running line. Sometimes it’s a bit more like a pin ball ricocheting along! It may not sound elegant, but if I am within the corridor it’s OK because I am still saving more time by not constantly having to stop to read the map than I lose by drifting right and left. I don’t need to go to the features to my right or left to follow them. A fence or open land may be 50 metres or more away, but it can still act as a Handrail or guide at a distance to steer me.

Remember that what you intend from the map as a straight line is usually a curve on the ground. Running through a corridor of features means you are constantly correcting the inevitable curves of your progress on the ground. Be extremely careful however, about deliberately trying to run in curves, that introduces even more error in your placement and is best avoided for most people.

Visualising a corridor frees you up from an earlier stage of orienteering navigation where routes are built in your mind as linking line and point features in a series of straight lines or zigzags. It also explains how the routes of top orienteers often flow through the terrain without actually going right up to firm features or exactly along line features.

This video from O-Ringen TV This is what a long leg in Östuna can look like (with Simon Eklov and Hilda Forsgren) (video No.10 in playlist), follows Hilda as she navigates a corridor of features on a long leg across complex terrain. Hilda’s explanation of her route as she goes is really clear.

Link to first video in playlist Learn to orienteer with Janne Troeng

There are other times when visualising such a virtual corridor is less helpful and fine navigation ticking off every feature you pass is the only way to find a control, especially on short legs in difficult areas.

Control flow is important but difficult to execute well

If you can know your exit direction you can move through a control smoothly minimising stopping and ideally not stopping at all. If you have had time to Plan-ahead for the next leg, then you can re-confirm that route choice as you move out of the control. At observation controls at major events the leading competitors are often not moving very fast near to and through controls, but they don’t stop either. However, if you need to stop to read the map more carefully then do it. Maybe you can flow smoothly through some controls and with others you will need to stand briefly and look more carefully. There is no point in moving smoothly through a control only to mess up the next Route Choice, so be flexible as to how you apply the concept of Control Flow.

Planning-ahead

If you are regularly struggling with simply executing legs reliably then planning-ahead is best left till your technique has improved further. There is no point in forcing extra errors by overloading your navigation ability by planning-ahead and thinking about too much to be able to safely return your concentration to the leg in hand. If you solve a leg in advance, let it go when you return to the current navigation and know that when you look at the leg again later you will be able to remember your solution and apply it. If a leg is too hard to solve on the run when planning-ahead, don’t worry, you have just highlighted one to take more care on later. If you do plan-ahead do it when safe to do so, such as walking up a hill if your head is clear enough or on a line feature. You must have a firmly identified Break Point such as a Catching Feature where you will return fully to the present leg or you will simply force errors on the current leg and gain no time overall.

Have the bigger picture in mind

Whilst it is often helpful to simplify your navigation to a corridor, a background sense of the bigger picture of the terrain can help a lot with relocation and confidence. If you have orienteered somewhere several times before you will hopefully feel that sense of having an overview of the area and will know where the tricky parts lie and thus where to be most careful. You can research this before an event by looking at previous maps and courses.

The background picture you might have could be that there is a major valley in the centre of the map. A quick look at the map confirms there is a wall running along its base. Dropping into the valley on approximately the right line looking for the crossing point is then all you need to know as you move quickly across that section of the leg. Just beware heading off line to the wrong crossing point if there is more than one.

Decide what type of leg you are facing

It’s not typical to orienteer on terrain where it is full-on fine navigation all the time. In every course there are easier legs and harder legs as the terrain and planning allows. Appraise a leg and be aware of what type of leg it is.

Is it just a Transit leg to get you to another part of the map?

Or is it set up because it will cause errors in Fine Navigation?

Or is it all about overall Route Choice with the chance to lose time by poor choice.

When you know what type of leg it is you can modify your speed and navigation accordingly.

A long leg may, of course, be a combination of route choice and fine navigation near the control.

If you know the map already from running there before or researching it, is the leg in an area where you know to be more careful?

The right approach for the course in hand

Think about the mix of techniques you will need for a course before you get to the start. Different courses present different demands and different strategies are appropriate. Urban sprint races make different demands from classic long forest races. A relatively short green course held on only modestly difficult terrain may not offer the opportunity to employ all the techniques. On a Green course Fine Navigation, solid Basic Routine, Simplification and good Control Flow and Route Choice are probably paramount.

A longer Blue or Brown course on Technical Difficult level 5 terrain with a variety of leg lengths, forest and open land might allow the use of every technique you can muster all in one race. Placement within a mental picture of the whole terrain, planning-ahead and balancing route choice against physical demands become more important considerations.

Every map is wrong and orienteering maps are amazing

Mapping and cartography necessarily involve a lot of subjective judgement. It is simply not possible to produce a map that translates 3-dimensional reality into a 2-dimensional form that will work perfectly when moved through in any direction and that will always match your oxygen starved perception of what is there on the ground. Vegetation varies with the seasons and grows and develops. True contours from say Lidar won’t match perceived contours on the ground and the mapper will often tweak a contour to show the shape better.

The mapper was not in oxygen debt when mapping, but you are when running! So, the question is one of how to handle the perceived certainty of different types of features. As a strategy to deal with these issues it is helpful to always bear in mind a hierarchy of which features are most likely to be perceived as “correct” when you encounter them.

| More certain Roads and tracks Buildings Rivers, lakes Large contour features and overall shape of the land | Less certain Vegetation boundaries Thickets Clearings Marshes Pits/ small depressions Boulders when in terrain with many boulders |

If a less certain feature is needed in navigation, be aware of other confirming features. If the control is on a less certain type of feature, then approach it from a firm attack point or along a run of more certain features.

Improve your distance estimation

To pace or not to pace, that is the question. (Pacing means counting your steps to measure distance).

In the early days of orienteering the maps were frequently quite poor. Often the only reliable way to find a point feature was to pace from a firm Attack Point. As maps have become better and richer in the information they convey it has become a less and less relevant technique. I know orienteers who still pace a lot. I know many who may only occasionally do so, such as in flat featureless terrain on a bearing. Orienteering styles do vary. In contrast, I never pace, nor do many orienteers I know. It simply doesn’t add helpful information to my navigation and my mental effort is better spent visualizing my placement in the terrain, or deploying another strategy. I’ll explain why.

Your distance measurement at speed from the map is not accurate. Your pacing on the ground is also inaccurate, being affected by many factors, such as what is under foot, the slope, your level of tiredness etc. That gives two sources of error straight away. It is hard to pace accurately beyond about 300 metres. Yet, with practice most people can reliably estimate at least 200 metres by sight, looking ahead. Having your head up and looking around at the right time makes a huge difference. The better your Mental Map the more confident you can be of your placement in the overall terrain. Then Notable Confirming features will help keep readjusting your position. Where Notable Features are lacking, then alternative strategies such as Aiming Off or deliberately cutting in a little early from a path and sweeping parallel to it are likely to be at least as successful as pacing to a falsely imagined definite point then turning in. Finally, counting is using processing capacity in your mind that is usually better employed in some other navigation task.

As maps have improved in accuracy and the level of detail shown, so orienteering technique has changed for experienced and elite competitors. Simon Eklov interviewing Mats Troeng explores this in the video below from O-Ringen TV, What has happened to maps since 1965? (No.6 in playlist)

Link to first video in playlist Learn to orienteer with Janne Troeng

Take a look at the examples of how the map of the same area has changed over time. Mats explains that as maps have changed, so too has orienteering technique. It has become possible to have a technique where you make constant adjustments of your line on the ground with compass and fine map details moving between notable features (or check points). Counting steps (Pacing) has become less relevant and few people use it anymore.

Mats Troeng has kindly supplied the map extracts so you can see the changes map by map from 1965 to 2019. The differences in the amount of detail and how precisely they are drawn are fascinating.

You can see the maps in more detail in the presentation What has happened to maps since 1965? in the Further Articles on Skills section.

So, if counting steps (pacing) works for you fine, but do think about whether it is actually is necessary and whether it distracts from your navigation overall.

Get more value out of your compass

Unless you happen to be a homing pigeon, the compass does something amazing that you can’t – it always stays lined up to north! The compass is strangely the most under used bit of orienteering help for most orienteers up to Intermediate level. Many people fall into the trap of thinking that they have orientated the map to north and then they can get on with navigating. Instead you need to refer to your compass constantly. With practice you can get much better at using it to constantly orientate your Mental Map to north. Also avoid the temptation to override the compass, you need to turn the picture in your head around to fit the truth the compass is telling you!

After you make a Plan for a leg, your visualization-or Picture and your Direction on the ground both need constant orientation to the terrain with the Compass.

Many people can see their compass better when running through rough terrain than the map. It can be a constant source of help. With a thumb compass you can either take a rough bearing or a more accurate one. To be accurate it requires most people to stop for 2 or 3 seconds to get the alignment very precise.

Rough Compass:

Understand and practice using the compass in different ways.e.g.

- Orientating the map for the overview of a leg.

- Confirming the exit route from a control

- Taking you between notable features on a leg

Fine Compass:

- Accurate bearings for when very precise direction is essential.

You will look at the map more often as you get better at orienteering, not less. While running, you get different information from the map at different points in the leg. You need to also get information from the compass every time too!

What level has my Visualization got to?

Are you solving one leg at a time and picturing as far as the next control?

Or do you have a rolling Picture that is always being updated, that goes beyond the next Notable Feature (check point) on route and the next control? And are you zooming in and out on the map to update different things as you run; your Picture of the whole leg, the next section of the leg, fine detail near the control, the wider picture of the shape of the terrain, your exit route from the control, the next Attack point etc…?

This requires always having a Picture of where you are going (a visualisation that is ahead of you). You will be continually making route choices, simplifying, building a mental map of your route and executing it. You will be looking at the map at times to plan the overall leg, at times to the visualise next section of the leg identifying the next notable feature, at times confirming your place in your visualisation. Before you complete one leg you are building a picture of the next one which you can flow into seamlessly through the control.

Where have you got to with your ability to visualise – (Picture ahead)?

Can you match your ability to visualize and to relocate against this set of descriptions? At an Advanced level you should be at the stage of Picturing Where am I going next? and quickly Relocating within a clearly defined area of the map with confidence. You will know where will you be in 100 metres and 200 metres and you will be able to place yourself within a 3 dimensional mental model of where you are in the terrain e.g. what you are flowing through.

Are you visualizing and navigating in an intermediate way or at an Advanced level? Have a look at these descriptions below:

A crucial difference between Advanced orienteers and Intermediate orienteers is that Advanced orienteers are visualizing well ahead of themselves all the time. They have a route in their mind around the forest and they pass the controls on that route slowing as little as possible. They are never thinking one leg at a time.

One way to estimate how much time your navigation is taking up, is to run a short technical course (maybe 2 to 3 km) then go round it again running as fast as you can, not punching controls and never stopping on the route. Treat it like a cross-country race. How much time difference is there? And what can you do to narrow the gap between your pure running speed and navigating speed?

It is worth giving an example before we finish this section. Tove Alexandersson, multiple women’s world champion, has also run against men’s elite and done very well. She has been able to beat elite men who can run faster than her. This suggests that she is able to navigate reliably much nearer to her maximum running speed in the terrain than most other elite orienteers, men or women. It is incredibly impressive and shows that while you need to be very fit to orienteer at the highest levels, it is how you put navigation and fitness together that matters.

In the next section Beyond Advanced, we look at Visualisation in more detail.